This summer I’ve been working on a series of non-digital with the Detroit Institute of Arts games for their family audiences and it’s fun to see how sometimes the concepts of good game design cross over so nicely from digital to analog games. (Sometimes they don’t- as seen in my paper game escapade at the crane estate from last year) but sometimes- like here- they really do.

We’re still in the prototype stage at the DIA but I thought I might write about our process of building so far to remind folks (and myself) that certain rules cross the borders for all kinds of UX design and a good design process never gets old!

STEP 1: “WITH” NOT “FOR”… INVOLVE YOUR TEAM AT EVERY STAGE!

One thing the DIA is incredible at is making sure their team is on-board and part of the design process. “WITH not FOR” is one of the best principles I’ve learned in designing games at nonprofit institutions. Even if you think the game that you meticulously designed on your own is better than what your team could do… it’s not. The best game is the one you can all agree on- because that’s the one that will be distrubuted to your visitors, even if the “game play” isn’t as clever. Your team knows things you may not and MOST importantly, you want to involve your front-line staff that’s working with the visitors. That may mean educators, guards or volunteers but they’re the ones that are distributing this product in the first place. You have to make sure it works for them so they can make it work for the visitor.

With that in mind, the DIA made sure that a game design workshop for their education staff and a game design “camp” for teens was part of my time with them. That set the stage for games to be a sanctioned, acceptable thing and encourages the DIA’s great education team to continue building educational games even when I’m not there.

STEP 2: KNOWN GAME DYNAMICS AND GOOD GRAPHICS

People are busy. Visitors are busy. I call it “16 seconds to nevermind.” You do not want your players to spend the bulk of their time LEARNING how to play your game, you want them to just play. That’s why it’s good to build games with rules that they may recognize right away. As the brilliant team from Fablevision once said, people respond to “known game dynamics. and market quality graphics.”

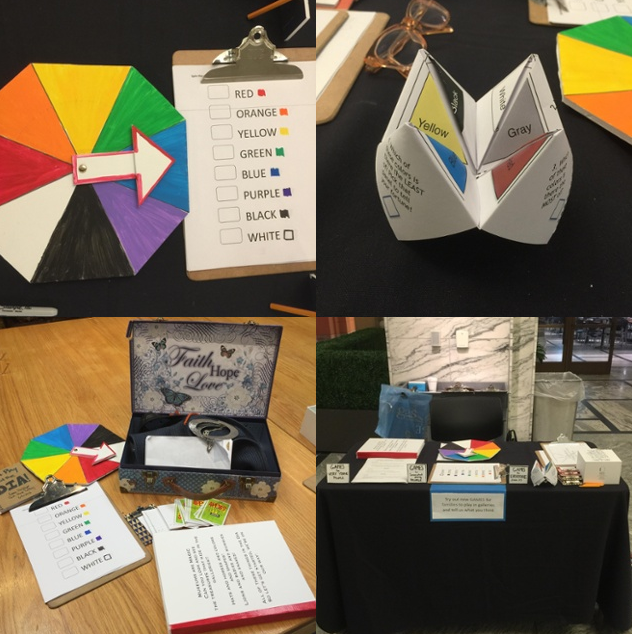

With that in mind, we decided to work on prototypes that would look familiar to players. Apples to Apples… but with art. A spinner… but with art. Dress up… but with art. Our most popular test game was an art fortune teller. The more complicated the instructions, the harder it was to get people to play.

Lemme show you:

I like the format:

“This game is called (X). It’s an (X) game and it’s sort of like (Y) except you (Z)”

For instance:

“This game is called Murder at the Met. It’s a mobile game that you play inside the Met galleries and it’s sort of like Clue except the victim, the weapon, location and murderer are all pieces of art in the gallery.” Nice, right? You get that.

Or

“This game is called the League of Extraordinary Bloggers. It’s a mobile game connected to five exhibits traveling around Children’s Museums in the US. It’s sort of like Where in the World Is Carmen San Diego except you’re tracking down a criminal with your team of teen sleuth bloggers in four Asian countries.”

Last, but not least…

“This game is called Apples to Art. It’s a card game that you can play in the DIA galleries. It’s sort of like Apples to Apples but the “red cards” are pieces of art in the galleries.”

If you’re building video games that people learn to play on their own in the privacy of their own home- the sky’s the limit. Make it as complicated as you want. If you’re building a game that people play in public, you have 16 seconds to never mind so you’re better get them through the door quickly!

STEP 3: TEST AND TEST AND TEST AND TEST AND TEST

The ideal number of people to test your game is 5 according to this– my favorite article about playtesting. But even ONE- just ONE play tester changes how you build your game and it just shocks me how many people build games and leave the testing until the very very end once they’ve already put tons of time into their design. Your testers will eat your first model for lunch. It’s a fact- no matter how good it seems, no matter how many times you’ve run it- they will find a way to break it and you’ll only know what that is if you test it.

We went into the DIA Prototype play test with 16 game prototypes… out of those 12, maybe 1 worked slightly the way I wanted it to. Over the course of four days we completely scrapped some ideas, built two completely new games from scratch, totally overhauled other ones and in the end- chose three games that I absolutely was not expecting. Who knew that if you give a 4 year old a color cube, they’ll gleefully throw it across the gallery? Who knew that if you give a 4 year old a block with a picture of a horse and tell them to go find horses, they look at you like you’ve handed them a magic quest? I did not know these things- and I wouldn’t still unless I was there testing and testing and testing again with the DIA team.

We’re ready to produce our prototypes and launch them, and there will be a whole new post about how to market your game and get buy-in from your community. But in the meantime I feel pretty honored to have been working with one of the all around coolest museums in the country.

So if you’ve been reading my blog for a while, you’ll say “Kellian, those tips are old news.” And they are- these are things that I’ve learned from years of building games with nonprofits and it’s always fun for me to see that they’s STILL TRUE!

So come September, you’ll have to come to the DIA and play some games!!

Leave a Reply